In the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, with record low interest rates and highly volatile equities, the term ‘alternatives’ became increasingly flexed.

In this perspective, what are the common denominators (if any) for alternative products?

Semanthic approach

« Alternatives » comes from the Latin word « Alternatum », derived from « alter », meaning « other ».

A priori, alternative investment assets are those which do not fall into the « traditional » asset classes e.g. cash, stocks, bonds that retail investors are most familiar with. Thus, alternatives are supposedly « exclusive » products designed to meet the specific needs of a miority of investors e.g. institutions, wealthy individuals.

In this respect, no need to wonder why so many « liquidative alternative » funds use the following marketing pitches like « Our fund incorporates the best of both worlds: Hedge fund like strategies and return potentials without the high fees and loss of liquidity ».

Being « alternative » does not necessarily mean being exclusive. It can merely mean being different (or pretending to be different), and quite unsurprisingly perform poorly.

Alternative products traditionnally fall in the following categories:

- Hedge funds

- Private equity buyouts

- Venture capital

- Other types: private equity real estate, private debt, private equity infrastructure, growth equity funds

Approach in terms of investment characteristics

Investment structure

Regulatory framework

The legal structures used by alternative investment funds differ significantly from most traditional fund arrangements e.g. mutual funds in the US, unit trusts in the United Kingdom, and UCITS funds in Europe.

En Europe, by the term « alternative funds » is meant all investment funds that are not already covered by the European Directive on Undertakings for collective investment in transferable securities (UCITS). This includes hedge funds, funds of hedge funds, venture capital and private equity funds and real estate funds.

The legal structure that alternative investment funds use is more flexible relative to traditional funds. They are not constrained by legal barriers imposed on traditional funds that limit their ability to use debt (leverage), short sell securities, invest in illiquid securities, or use derivatives when seeking to implement their investment strategies.

Investment lifespan

- Most alternative products use closed-end fund structures with a fixed lifespan (typically 10-15 years). All of the value of the investment is returned to investors within this timeframe, who must then identify new investment opportunities to reinvest the capital in.

- Hedge funds are an exception: they usually offer open ended funds in that the capital is automatically reinvested with the fund unless the investor requests that the capital be returned to them.

Cash flow patterns

- Alternative investments have more unpredictability in the size and timing of cash flows than that of traditional funds. Whereas cash invested in a traditional fund is usually fully invested within one business day, most alternative investment funds accept cash commitments from investors (no cash is transferred to the fund until it needs the cash to make an investment). The cash will be invested (« capital call« ) over a period of time (often years).

- The return of capital (a “distribution”) to an investor is unpredictable, since fund managers cannot predict the timing or price of an asset in advance. The resulting cash flow pattern is known as a j-curve, which is illustrated below.

Liquidity constraints

Most alternative products use closed-end fund structures that do not permit investors to withdraw their capital from the fund due to the illiquid nature of the investments. However, investors can sell their stake to a secondary fund, which specializes in such transactions.

Fee structures

Most alternative investment funds have two primary fees: management fees and performance fees.

- Management fee: Fund managers usually receive fees of 1-2% of raised or invested capital per annum. Such fees are intended to cover the costs of operating the fund. Fees in excess of these costs are retained by the firm that manages the fund, which can create an incentive to raise large funds.

- Performance fees (also known as carry): Fund managers typically receive 20% of net profits generated by the fund over its lifespan, once the hurdle rate (discussed below) has been met. Sharing in the profits serves to align the interests of the fund manager and the underlying investor.

- Hurdle rate (also known as a high watermark or preferred rate of return): Most fund agreements stipulate a hurdle rate of 7-8%. Fund managers do not receive performance fees until they meet the hurdle rate. As the hurdle rate is calculated over the whole life of a fund, sub-par returns in one year need to be matched with outsized returns in following years. This incentivizes fund managers to aim for high absolute returns and take a long-term view.

Performance metrics

Alternative investors use different performance metrics than those used by traditional funds. The difference reflects the fact that the former have control over the timing of an investment, but traditional managers do not (the investor determines this).

- Traditional funds measure returns using the time weighted method, which ignores how much cash was invested and simply computes returns based on the value of a security at two points in time.

- Alternative investors use the money weighted return method (aka internal rate of return, IRR), which weights returns based on the size of the cash inflows and outflows over time. In turn, alternative investment funds are typically measured by the rate of return they are able to generate over a period of time and a cash flow multiple, which compares how much cash was returned to an investor relative to how much they started with.

Investment life cycle

The investment life cycle for most types of alternative investments is usually much longer and involved than that of a traditional investment. The steps and the order they are taken in are shared by all alternative investments, but there is tremendous variance between how each asset class executes each step and how long each step can take.

A common role in society and the economy?

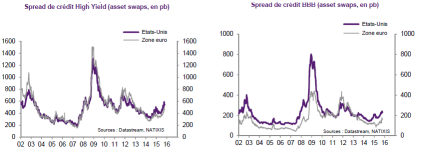

Capital markets

- efficient allocation of capital to long-term, illiquid or risky investment assets that might otherwise be underfunded by traditional investors.

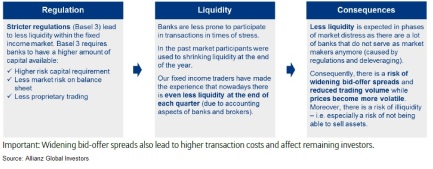

- The trading volume of hedge funds strengthens price discovery and reduces bid-ask spreads (transaction costs). They do this by serving as counterparties willing to buy or sell assets that might otherwise have remained illiquid.

Real economy

- Economic impact: innovation, competition

- Corporate gouvernance: many alternative investors have a positive effect on corporate governance e.g. activist hedge funds. This view would need to be nuanced, though.

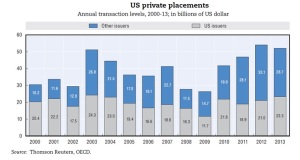

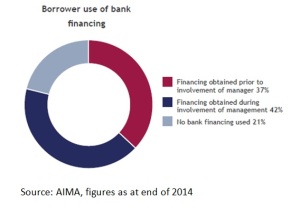

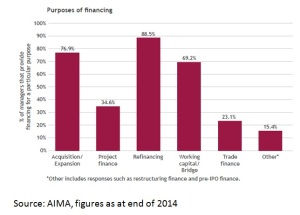

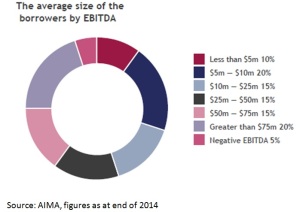

Shadow lending

Over the last few years, an increasing number of firms expanded into providing debt to businesses, an area traditionally dominated by banks. (cf article: Private Placements: not so « private » any more… »). This disintermediation process is part of shadow banking /shadow lending.

Sources:

World Economic Forum – Alternative Investments 2020: An Introduction to Alternative Investments

PWC – Alternative Asset Management 2020

BlackRock, 10 Myths surrounding alternative investments